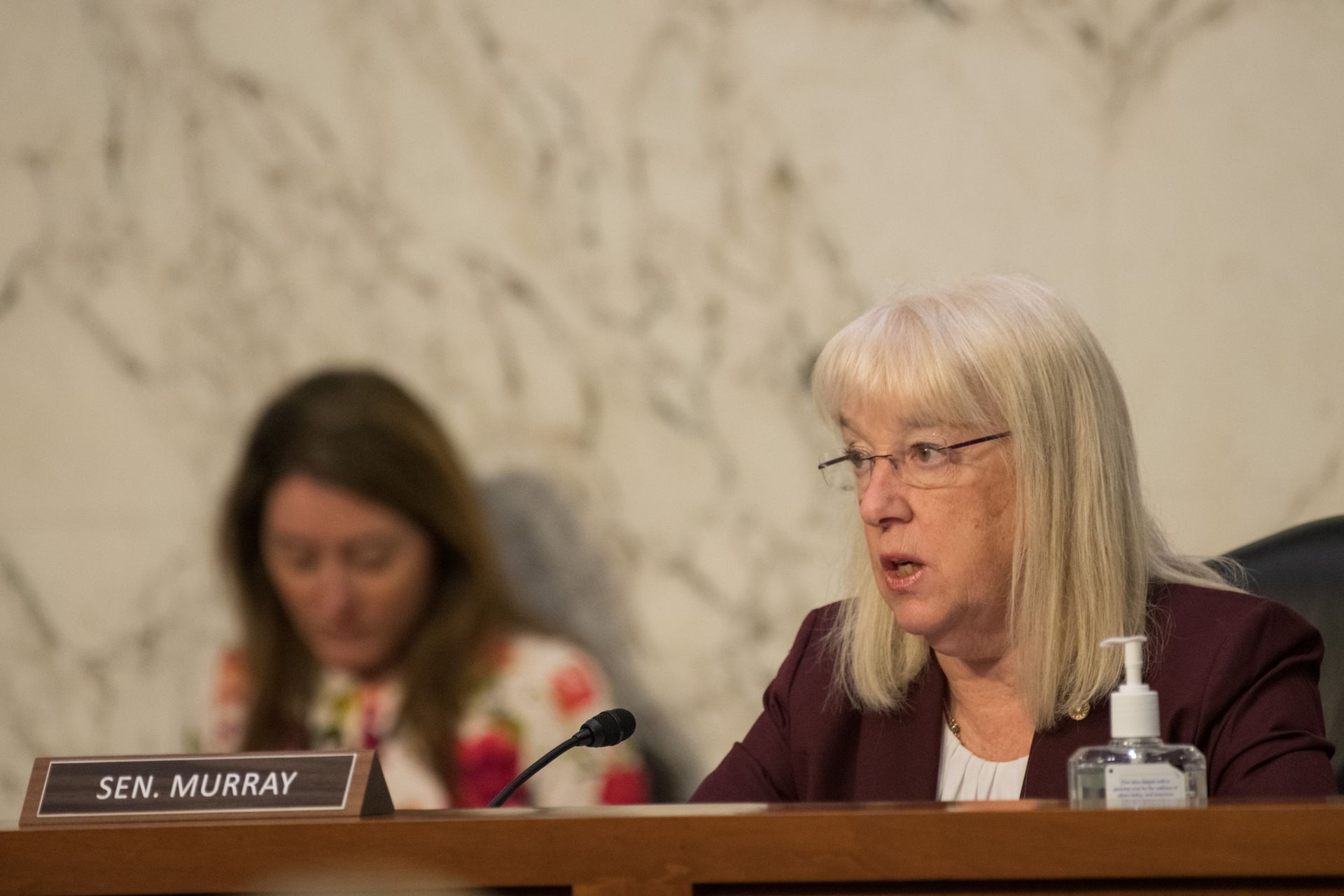

Senators applaud critical forward progress, outline further steps to strengthen proposed regulations

(Washington, D.C.) – Today, U.S. Senator Patty Murray (D-WA), Chair of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP), led 22 of her colleagues in commenting on the Department of Education’s proposed rules to expand and improve student debt relief programs. In a letter to Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona, the Senators applauded the Department’s efforts to provide and expand relief to borrowers whose schools closed or defrauded them, borrowers working in public service, and borrowers who are totally and permanently disabled. The Senators encouraged additional steps to improve the Department’s student debt relief programs and ensure borrowers can access the relief they are owed.

“The Department’s proposed rules will help to provide additional relief to struggling borrowers, protect students and taxpayers from fraud and abuse committed by institutions, and ensure our federal student loan program fulfills its promise to put higher education within reach for more students without subjecting them to complex, burdensome, or punitive requirements that make it harder to get the relief they are owed,” wrote the Senators. “This proposal represents an enormous step forward for students and borrowers, and, when finalized, it will help ensure government benefits and programs function as Congress intended.”

In their letter, the Senators commended the Biden administration’s proposals to deliver and expand relief for these borrowers—steps Senator Murray and her Democratic colleagues urged the Department to take in a letter last year.

They also detailed additional steps the Department should take to strengthen its proposal. In particular, the Senators recommended steps to further strengthen its borrower protection rule, further expand relief for borrowers seeking a closed school discharge and eligibility for the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, eliminate interest capitalization on all loan types, and further protect students’ right to seek relief in court. The Senators also urged the Department to continue working to fix the income-driven repayment system, crack down on bad actors, and provide as much relief as possible to borrowers.

“As the Department works to finalize these regulations, we urge you to build on this progress by strengthening rules in other vital areas, including income-driven repayment and gainful employment,” added the Senators. “We also urge the Department to continue efforts to protect borrowers outside the rulemaking process, including by immediately and efficiently using its current oversight and enforcement authorities to reign in bad actors and provide as much relief as possible to borrowers.”

The letter, led by Senator Murray, was also signed by Senators Schumer (D-NY), Baldwin (D-WI), Markey (D-MA), Wyden (D-OR), Reed (D-RI), Coons (D-DE), Hirono (D-HI), Cardin (D-MD), Warnock (D-GA), Gillibrand (D-NY), Warren (D-MA), Lujan (D-NM), Casey (D-PA), Whitehouse (D-RI), Blumenthal (D-CT), Smith (D-MN), Cortez Masto (D-NV), Padilla (D-CA), Brown (D-OH), Durbin (D-IL), Van Hollen (D-MD), and Rosen (D-NV).

The Senators’ full letter is available HERE and below:

The Honorable Miguel Cardona

Secretary of Education

U.S. Department of Education

400 Maryland Avenue, S.W.

Washington, D.C. 20202

Docket ID ED-2021-OPE-0077

Dear Secretary Cardona:

We write in response to the U.S. Department of Education’s (“Department”) proposed rules regarding debt relief for borrowers whose schools closed or defrauded them, borrowers who are totally and permanently disabled, and borrowers who are public service workers. The Biden-Harris Administration’s proposed regulations for student loan discharge programs make tremendous progress in providing and expanding relief to borrowers, and we’re pleased to see Senate Democratic priorities, as outlined in the July 1, 2021, letters on program integrity and debt relief, reflected in this proposal.[1] We applaud the proposal’s improvement and streamlining of student loan relief programs and commend the Department’s efforts to support student loan borrowers.

For far too long, students who face a variety of barriers have been cheated by predatory for-profit colleges, denied their day in court due to mandatory arbitration agreements, and denied debt relief because of standards that are impossible to meet. Borrowers have seen their balances balloon due to interest capitalization, they have had their lives altered by sudden college closures, and they have faced burdensome and overly-complicated requirements to access debt relief. This Administration has demonstrated its commitment to helping borrowers access the relief they are entitled to and holding institutions accountable for misconduct, including through this draft rule. This proposal represents an enormous step forward for students and borrowers, and, when finalized, it will help ensure government benefits and programs function as Congress intended.

For these reasons, we strongly support the Department’s proposed rules for student loan relief programs. Below, we provide detailed input on each of the draft regulations proposed by the Department. We also urge the Department to continue efforts to protect borrowers outside the rulemaking process, including by immediately and efficiently using its current oversight and enforcement authorities to reign in bad actors and provide as much relief as possible to borrowers.

Borrower Defense to Repayment

After years of deregulation of the “borrower defense” rule under the previous Administration, which undermined protections for defrauded borrowers and relentlessly denied them relief, we commend the Biden-Harris Administration for reversing course and proposing the strongest borrower defense rule we have ever seen.

The previous Administration required borrowers to meet an extremely difficult standard to prove their colleges caused them harm and, as a result, only 7.5 percent of borrower defense claims were estimated to be approved, down from 65 percent under the prior rule.[2] This was so unpopular that Congress—in a bipartisan effort—passed a Congressional Review Act resolution to overturn the rule, which was later vetoed by President Donald Trump.[3]

We commend your efforts to redress the harms this deregulatory regime caused borrowers—including borrowers from low-income families, first-generation students, students of color, and veterans—who have been targeted and lied to by predatory for-profit institutions. These borrowers deserve to be able to access the loan relief they are entitled to through a fair and streamlined process.

Specifically, we strongly support the establishment of a single and streamlined borrower defense standard that better captures the full scope of institutional misconduct relevant for a borrower defense claim. To date, the review process for borrower defense claims has been overly burdensome, with inconsistent regulatory standards depending on loan disbursement date. This has contributed to inequities amongst similarly situated borrowers and lengthy delays in the adjudication of claims, leaving borrowers waiting far too long for relief. The establishment of a single standard with clearer and expanded grounds for borrower defense claims represents a tremendous step forward in protecting consumers and the integrity of the federal financial aid programs. We are also pleased to see that misconduct related to substantial omission of fact and aggressive and deceptive recruitment can serve as a basis for borrower defense under the Department’s draft rule.

Additionally, the restoration and strengthening of a group process for borrowers seeking discharge, the establishment of a set timeline for adjudication of both group and individual claims, and the enhanced authorities for the Department to recoup the cost of discharges from predatory institutions are welcome and necessary changes. We support the Department’s approach to establishing a presumption of full discharge in place of the partial relief approach utilized under the last Administration and eliminating the limitations period for borrowers, both of which have created major barriers that have unnecessarily prevented borrowers from accessing the relief to which they are entitled.

We remain concerned about the need to protect borrowers from predatory for-profit colleges that are defrauding borrowers at scale and urge you to allow legal assistance organizations, in addition to state attorneys general, to bring forth group claims. Additionally, we encourage you to suspend interest accrual immediately for all borrowers with a pending borrower defense claim. Under the draft regulations, the Department proposes to cease interest accrual for borrowers filing an individual claim only after their claim has been pending for 180 days. Borrowers covered by group claims, meanwhile, would see their interest paused immediately, a distinction that the Department states is based on the premise that not all group members proactively apply for borrower defense. However, no borrower opts into being defrauded or misled by their institution, and no borrower subjected to misconduct should have to see their loan balance balloon while they wait for the Department to take action. We further encourage you to clarify that, if the Secretary reopens a borrower defense application under which a borrower received partial forgiveness, the Secretary may not reduce or rescind previously provided forgiveness. This change would appear to be in alignment with the Department’s intent, given that the preamble states, “a borrower only stands to benefit from the Secretary reopening a borrower defense application that was fully or partially denied.”

Lastly, we encourage you to continue to use existing enforcement authorities to hold institutions accountable for engaging in misconduct and wasting taxpayer dollars. We are encouraged by the Department’s ongoing efforts to deliver group discharges of borrower defense claims and look forward to more relief for groups of students who are subject to the same findings of misconduct.

Mandatory Pre-dispute Arbitration and Prohibition of Class Action Lawsuits Provisions in Institutions’ Enrollment Agreements

As part of its deregulatory agenda, the previous Administration removed restrictions banning the use of pre-dispute arbitration agreements and class action lawsuit waivers, thereby allowing institutions to deny students their day in court by requiring them to give up their rights as a condition of enrollment. Instead, students at these institutions are forced to waive their right to pursue class action lawsuits or are required to resolve disputes through mandatory arbitration proceedings. Furthermore, the outcomes of arbitration proceedings are often kept secret—effectively hiding predatory practices from the public and regulators, including the Department. As outlined in the July 1, 2021, letter from 12 Senate Democrats on program integrity, for-profit colleges have a long track record—unique compared to other sectors of higher education—of imposing these mandatory arbitration agreements and class action lawsuit waivers. [4] For example, a 2016 study examining enrollment contracts from 217 institutions found mandatory arbitration clauses in 98 percent of contracts at for-profit institutions, compared to just seven percent at nonprofits.[5] No public institutions examined in the study required students to settle disputes through arbitration.[6]

We applaud the Department’s proposal to reinstate the ban on mandatory arbitration agreements and class action waivers for lawsuits relating to acts or omissions regarding the making of the Federal Direct Loan and the provision of educational services for which such loans are obtained. Since forced arbitration is prevalent in for-profit colleges,[7] the draft proposal to prohibit forced arbitration clauses and class-action waivers will benefit many borrowers attending for-profit colleges. Additionally, the proposal will have a greater impact on Black students who are overrepresented at for-profit schools, by a near 15-percentage point difference, compared to public and private universities.[8] We further commend the collection and public disclosure of arbitral and judicial records related to borrower defense claims. These disclosures will enhance transparency regarding the outcomes of arbitrations, support oversight efforts, and help ensure prospective students and their families have access to information about past instances of institutional fraud and misrepresentation.

As you work to finalize the pre-dispute forced arbitration and class action waiver bans, we encourage the Department to make clear that institutions must use the notice language included in the final regulations verbatim and without conditions when providing the required notices to borrowers. We further urge you to clarify the timing of notices sent to borrowers who previously attended institutions that maintained mandatory arbitration and class action waiver requirements. These students should be made aware as quickly as practicable that their rights to pursue claims in court—both as an individual and as part of a class—have been restored.

Public Service Loan Forgiveness

We commend the Department’s efforts to expand Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) eligibility and codify recent improvements in the consideration of qualifying payments and the application process. As expressed by 23 Senate Democrats in the July 1, 2021, comment letter on debt relief, Senate Democrats support closing holes in PSLF eligibility, removing overly restrictive regulations on qualifying payments, and making it easier for borrowers working in public service to obtain the PSLF forgiveness they are entitled to under the Higher Education Act (HEA).[9]

The proposed rule makes critical improvements to the PSLF program by codifying parts of the Biden-Harris Administration’s limited PSLF waiver, which has already resulted in at least $9 billion of forgiveness for more than 146,000 public servants and more than 1 million borrowers receiving, on average, one additional year of credit toward PSLF.[10] Specifically, we applaud allowing more payments to qualify for PSLF including counting payments made prior to consolidation and payments made in multiple installments or outside the 15-day period in current regulations toward PSLF forgiveness. Additionally, the Department’s proposed definition of full-time employment will protect borrowers from being subject to a higher full-time definition set by their employer, ensure eligible borrowers working for multiple employers can obtain relief, and clarify how the Department will calculate the equivalent weekly hours worked for borrowers who are non-tenured instructors.

While we are encouraged by the Department’s necessary proposal to count certain periods of deferment and forbearance toward PSLF, we urge you to count all such periods toward PSLF to reduce unnecessary complexity, address administrative failures by student loan servicers, and fulfill the program’s goal of alleviating the burden of federal student loans for borrowers in public service.[11] Unfortunately, federal investigations have found that student loan servicers have steered borrowers into forbearance, made errors during loan transfers, and failed to advise borrowers about their options to enroll in income-driven repayment plans, under which monthly payments—even if they are $0 payments—count toward PSLF.[12] Borrowers should not lose progress toward forgiveness when a servicer pauses a borrower’s payments to process paperwork, nor should borrowers be penalized for following bad advice from a servicer or experiencing other types of industry misconduct.

Under the proposed regulations, the Department contemplates the inclusion of for-profit early childhood education (ECE) employers as qualifying employers for the purposes of PSLF. In response to the Department’s request for comments on this proposal, we support the inclusion of for-profit ECE employers because early childhood educators employed by for-profit ECE employers fundamentally provide a public service to the nation. In addition to providing critical services to educate and care for young children, early childhood educators also play an integral role in supporting working families, businesses and the nation’s economy. According to American Community Survey data, nearly two-thirds of children younger than age six have all parents in the labor force, making access to quality, affordable child care a necessity for working families across the country.[13] Section 455 (m)(3)B)(i) of HEA includes “early childhood education (including licensed or regulated child care, Head Start, and state funded pre-kindergarten)” as part of the statutory definition of a “public service job”, demonstrating Congress’ intent to specifically include the early childhood workforce as eligible for PSLF. The child care sector is a mixed-delivery system that relies at least in part on non-public providers.[14] Additionally, many family child care providers are small businesses with one early childhood educator as both the sole proprietor and sole employee. The vast majority of child care providers are small businesses operating on razor thin profit margins that are usually less than 1 percent.[15]

Moreover, when Congress authorized the PSLF program in 2007, the intent was to incentivize employment in public service positions that were presumed to generally have lower wages than other occupations. Today, early childhood educators, who are almost entirely women and 40 percent of whom are women of color—typically earn poverty-level wages despite having highly specialized skills and postsecondary education.[16] Staffing challenges due to inadequate wages for early educators are fueling a nationwide shortage of child care. The inclusion of for-profit early childhood education employers as qualifying employers for PSLF could help recruit and retain highly qualified early educators and strengthen the workforce to ensure that child care remains available to the children and families who need it.

The Department should take a multifaceted approach to implement this measure. For example, the Department should collaborate with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to identify methods to collect Employer Identification Numbers (EINs) for Head Start and Early Head Start programs.[17] Additionally, the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) Act requires states to have in effect licensing requirements applicable to child care services provided within the state.[18] In addition, HHS regulations require each state lead agency to maintain a website with a “localized list of all licensed child care providers” in the state.[19] In turn, HHS operates a national website that links to state databases of child care providers.[20] The Department should consult with HHS on whether and how these state databases may be used to help verify licensed and regulated child care programs. Where practicable, the Department and HHS should automate information-sharing related to qualifying employers and clarify that borrowers working for for-profit ECE employers may pursue the reconsideration process outlined in the proposed rule if they are denied PSLF relief.

We also support extending PSLF eligibility to certain self-employed independent contractors who are working on a full-time basis with a qualifying employer, but are not employed directly by the qualifying employer. For example, as noted in the preamble, public defenders and doctors in rural nonprofit hospitals who are independent contractors are not currently eligible for PSLF. Eligibility requirements should be adjusted to account for such types of circumstances particularly in public and nonprofit settings, in which borrowers are providing a public service with a qualifying employer but are not compensated directly by the qualifying employer. Additionally, externally sponsored fellows at not-for-profit organizations and public agencies, such as early career attorneys in public service roles, should be eligible for PSLF. These borrowers are not considered “employees” under the Department’s draft PSLF regulations despite working for a qualifying employer and contributing to the public good. We believe the treatment of contracted fellowships should be distinct from other types of more lucrative, contracted positions in which borrowers may be providing a service to the qualifying employer while being compensated by a non-qualifying employer. In the case of independent contractors, organizations are likely to be willing to sign PSLF forms on their behalf given that they are likely already completing PSLF forms as qualifying employers and often track the number of hours worked for the independent contractors they hire. The Department should clarify the definition of “employee” includes contractors, working for a qualifying employer, who may receive tax forms other than W-2s, including 1099 forms.

Relatedly, we support the Department’s ongoing efforts to provide relief to public service workers through the limited PSLF waiver and urge the Department to extend the application deadline for the waiver to align with the implementation of the new changes being made under the Department’s forthcoming rules.

Interest Capitalization

As the Department’s preamble explains, interest capitalization—in which some or all of a borrower’s unpaid interest is added to their principal—can contribute to growing balances, extended time to repayment, and a higher risk of delinquency and default, leading to financial and psychological challenges that hamper successful loan repayment.[21] Furthermore, the Department’s data demonstrate that interest capitalization is particularly harmful for Black borrowers, Pell Grant recipients, borrowers from low-income families, and borrowers who left college without completing a degree or credential.[22]

The Department’s proposal to remove interest capitalization where not required by statute represents a vital step in preventing borrowers’ debts from growing over time and reducing racial and socioeconomic disparities in loan repayment outcomes. We applaud the Department’s proposal and encourage you to build on these efforts in the forthcoming regulations for income-driven repayment by eliminating negative amortization on all loan types, as proposed in the July 1, 2021, letter from 23 Senate Democrats on debt relief.[23] We additionally encourage you to remove capitalization when a borrower in the Pay As You Earn (PAYE) repayment plan is determined to no longer have a partial financial hardship, as it is currently required (and maintained in the Department’s draft rules) under 34 CFR 685.209(a)(2)(iv). The Department should also examine whether it is still necessary to maintain language capping the amount of interest capitalized under the alternative repayment plan at 34 CFR 685.208(l)(5), as well as the reference to that provision at 34 CFR 685.202(b)(2), as redesignated by the Department’s draft rules, given the proposed striking of 34 CFR 685.202(b)(4).

Total and Permanent Disability Discharges

As outlined in the July 1, 2021, letter from 23 Senate Democrats on debt relief, current regulations have created unnecessary barriers for borrowers who are entitled to a total and permanent disability (TPD) discharge under the HEA.[24] We strongly support the Department’s proposal to expand the types of acceptable documentation and the list of medical professionals who are authorized to certify a borrower’s eligibility for a TPD discharge. We also commend the Department’s proposed changes to expand the categories of borrowers who may qualify for discharge in alignment with congressional intent. Additionally, we support that the Department’s draft rule would make it possible for qualifying borrowers to access a TPD discharge without an application and encourage the Department to automate the TPD process as much as possible wherever the Department can do so.

Under the current TPD regulations, borrowers who receive a discharge are subject to a three-year post-discharge monitoring period during which a borrower’s discharged loan is reinstated if their income rises above a certain level or if they subsequently receive a federal student loan or a TEACH Grant. As the Department’s preamble noted, however, many borrowers have had their loans reinstated due to paperwork issues and not because they had earnings above the threshold for reinstatement. We support that the Department has proposed eliminating the three-year income monitoring period as proposed in the July 1, 2021, letter from 23 Senate Democrats on debt relief.[25] This change will remove unnecessary and harmful barriers that have prevented borrowers from getting the much-needed relief that they are entitled to under the law.

However, the Department’s draft rules propose to maintain the reinstatement of loans for borrowers who obtain additional loans or TEACH Grants within three years of receiving TPD discharge. During negotiations, non-federal negotiators recommended reducing the three-year monitoring period to one year, but the Department’s preamble stated that they “[had] not been presented with a reason to change our current position on having a three year limitation on borrowers taking out additional title IV loans.” It appears that the Department intends to use loan reinstatement as a deterrent to discourage future borrowing, but in practice, this policy risks imposing a hefty penalty on borrowers who may not understand the consequences of borrowing new loans.[26] This policy may be particularly harmful for borrowers who discover only after re-enrollment that they will not be able to complete their chosen program or secure work in their desired field.

We therefore encourage the Department to revisit this issue, to examine the frequency and impact of loan reinstatement due to subsequent borrowing, and to consider shortening the monitoring period to one year, as suggested by non-federal negotiators. This change would provide more certainty to borrowers who receive a TPD discharge and align with the Department’s overarching efforts to bolster borrowers’ access to debt relief and minimize harmful and punitive consequences associated with borrowing.

Closed School Discharges

The closure of an institution of higher education can have severe and life-altering consequences for enrolled students, even as corporate executives and private equity owners escape accountability, as witnessed during the precipitous closure of ITT Technical Institutes and Corinthian Colleges.[27] It is vital that the Department adopt a robust closed school discharge (CSD) rule and maintain a reliable and straightforward CSD process in order to ensure taxpayers and borrowers are not left paying the price when an institution collapses. As part of this effort, 23 Senate Democrats have called on the Department to reinstate the automatic CSD process and process discharges more quickly; eliminate restrictions that prevent students who transfer from receiving a CSD; and extend the look-back window that allows borrowers who left an institution prior to its official closure to access a CSD.[28]

We are encouraged by the Department’s proposals to reinstate automatic closed school discharges and extend the look-back window from 120 to 180 days, with the option for a further extension in exceptional circumstances. We also appreciate and support the clarifications regarding what constitutes an exceptional circumstance, how the Department will identify a school’s closure date, and the definition of a program for purposes of the CSD regulations. However, while we appreciate the Department’s proposal to eliminate provisions that deny a CSD to students who transfer, we are concerned that the Department’s alternative—namely, denying a CSD to students who accept and complete a teach-out plan or agreement—will have similarly harmful consequences.

Section 437(c)(1) of the HEA requires that the Secretary of Education discharge the loans received by any student who “is unable to complete the program in which such student is enrolled due to the closure of the institution” and makes no mention of transfers to other institutions.[29] As 23 Senate Democrats pointed out in the July 1, 2021, letter on debt relief, the current regulations denying a CSD to borrowers who transfer to another institution within 3 years of a college’s closure are inconsistent with the statute and should be eliminated.[30] Similarly, the HEA does not condition the receipt of a CSD on the rejection of a teach-out plan or agreement. For this reason, and the reasons outlined below, we urge the Department to eliminate these unnecessary restrictions and adopt regulations consistent with the HEA that provide an automatic CSD for any student who is unable to complete their program due to institutional closure, regardless of whether they subsequently transfer or accept or complete a teach-out plan or agreement.

Under the Department’s regulations, a teach-out plan is only required to provide for the “equitable treatment of students” and include general details such as a list of currently enrolled students, academic programs offered by the institutions, and other institutions offering similar programs.[31] A student who accepts a teach-out plan does not have any assurance that they will be able to complete their program, much less that program completion will be possible in a timely fashion and with minimal disruption. It is unclear what the Department intends to accomplish by excluding students who “complete” a teach-out plan, but given that those students are not necessarily provided any pathway to transfer previously earned credits or to continue and complete their programs, it seems contrary to the Department’s stated goals to deny them access to an automatic CSD.

Teach-out agreements, meanwhile, are subject to more stringent requirements, but still only provide for a “reasonable opportunity” for program completion and do not ensure that students will be able to transfer all (or even a majority) of their credits or access programs that are reasonably affordable (or even comparably priced).[32] As such, it is unreasonable to assume that all students who accept and complete a teach-out plan or agreement will receive their desired credential in a comparable program of study without suffering the consequences of an institutional closure. Even those students who do complete a comparable program through a teach-out plan or agreement may still experience major disruptions and incur significant costs re-taking coursework that does not transfer. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that students pursuing a teach-out plan or agreement will receive a credential that is of comparable value in the workforce as what they might have received had their original institution not closed, particularly given the reputational damage often associated with the closure of an institution. There is also no guarantee that a credential earned through a teach-out agreement will have the same programmatic accreditation as the student’s original program or that it will fulfill any relevant state licensure requirements.

Accordingly, we urge the Department to strike the provisions denying a CSD to students who complete a teach-out plan or agreement, and, to the greatest extent practicable, accelerate the timeframe for providing automatic discharges given that the one-year monitoring period would no longer be necessary. If the Department is unwilling to make that change, we urge you to, at a bare minimum, remove the exclusion of students who complete teach-out plans and limit the exclusion of students who complete teach-out agreements to only those students who actually complete a comparable program within a reasonable amount of time (e.g., one year). The Department could also limit the exclusion to students who are able to transfer most or all of their previously earned credits. When a student takes longer to complete their program, or is unable to transfer most or all of their credits, they incur more costs (in both time and money) at their new institution retaking or completing additional credits and experience fewer benefits from the education they received at their previous institution prior to its closure. Lastly, if the Department does opt to restrict access to a CSD based on subsequent enrollment, it should, to the greatest extent practicable, automate data collection (e.g. by using CIP codes and NSLDS enrollment status) rather than requiring new reporting, which may be particularly challenging once institutions have closed and are no longer tracking students who have left.

False Certification Discharges

When an institution falsifies a student’s eligibility for Title IV aid, it should be the institution—not the student—who pays the price. However, as the Department’s preamble explains, the current false certification regulations include two sets of eligibility criteria, creating confusion and establishing different standards and processes for false certification discharges depending on when the loans were first disbursed. Additionally, some borrowers who may be eligible may not have received a discharge because of the difficulty in navigating unnecessarily complex requirements. Therefore, we applaud the Department’s proposal to streamline the false certification discharge process by providing one set of regulatory standards covering all false certification discharge claims. We also support the expansion of acceptable documentation, clarification of applicable dates, and creation of a group false certification discharge process included in the draft rules. These proposals represent a significant step forward for students who have been coerced or defrauded by their schools.

The Department’s proposed rules will help to provide additional relief to struggling borrowers, protect students and taxpayers from fraud and abuse committed by institutions, and ensure our federal student loan program fulfills its promise to put higher education within reach for more students without subjecting them to complex, burdensome, or punitive requirements that make it harder to get the relief they are owed. As the Department works to finalize these regulations, we urge you to build on this progress by strengthening rules in other vital areas, including income-driven repayment and gainful employment. Thank you for your attention.

Sincerely,

###

[1]Sen. Richard Durbin et al. to Sec. Miguel Cardona, July 1, 2021, https://www.durbin.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Consumer%20Protections%20and%20Program%20Integrity%20Dem%20Caucus%20Letter%207.1.21.pdf; Sen. Patty Murray et al. to Sec. Miguel Cardona, July 1, 2021, https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Senate%20Dem%20Student%20Debt%20Relief%20Comment%20Letter%20to%20ED%201-July-2021.pdf.

[2] 87 FR 41883, https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2022-14631/p-90.

[3] “Durbin Statement On Trump’s Veto Of Bipartisan Congressional Resolution Overturning DeVos Borrower Defense Rule,” U.S. Senator Dick Durbin of Illinois, May 29, 2020, https://www.durbin.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/durbin-statement-on-trumps-veto-of-bipartisan-congressional-resolution-overturning-devos-borrower-defense-rule.

[4] Sen. Richard Durbin et al. to Sec. Miguel Cardona, July 1, 2021, https://www.durbin.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Consumer%20Protections%20and%20Program%20Integrity%20Dem%20Caucus%20Letter%207.1.21.pdf.

[5] Tariq Habash & Robert Shireman, “How College Enrollment Contracts Limit Students’ Rights,” The Century Foundation, April 28, 2016, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-college-enrollment-contracts-limit-students-rights/.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Tomás Monarrez & Kelia Washington, “Racial and Ethnic Representation in Postsecondary Education,” Urban Institute, June 18, 2020, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/racial-and-ethnic-representation-postsecondary-education.

[9] Sen. Patty Murray et al. to Sec. Miguel Cardona, July 1, 2021, https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Senate%20Dem%20Student%20Debt%20Relief%20Comment%20Letter%20to%20ED%201-July-2021.pdf.

[10] Federal Student Aid, “Public Service Loan Forgiveness Data: June 2022”, August 9, 2022. https://studentaid.gov/data-center/student/loan-forgiveness/pslf-data; 87 FR 41878

[11] Alexandra Hegji, “The Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program: Selected Issues” Congressional Research Service, October 29, 2018, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45389.

[12] U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Federal Student Aid: Education Needs to Take Steps to Ensure Eligible Loans Receive Income-Driven Repayment Forgiveness,” GAO-22-103720, March 21, 2022, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-103720.

[13] United States Census Bureau, “Percent Of Children Under 6 Years Old With All Parents In The Labor Force, https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/ranking-tables/

[14] A. Rupa Datta, Z. Gebhardt, C. Zapata-Gietl, “National Survey of Early Care & Education: Center-based Early Care and Education Providers in 2012 and 2019: Counts and Characteristics.” Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, September 2021, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/cb-counts-and-characteristics-chartbook_508_2.pdf.

[15] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “The Economics of Child Care Supply in the United States,” September 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/The-Economics-of-Childcare-Supply-09-14-final.pdf.

[16] The Center for the Study of Early Childhood Employment, “Early Childhood Workforce Index, 2020”, https://cscce.berkeley.edu/workforce-index-2020/; Maureen Coffey, “Still Underpaid and Unequal.” Center for American Progress, July 19, 2022, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/still-underpaid-and-unequal/. According to this report, seventy-six percent of ECE educators have some kind of professional credential or postsecondary degree.

[17] The SF-424 form is part of the standard Head Start application package that requests applications to provide their EIN. Application for Federal Assistance SF-424, OMB No. 4040-0004, expiration date December 31, 2022, https://apply07.grants.gov/apply/forms/readonly/SF424_2_1-V2.1.pdf.

[18] 42 U.S.C. § 658E(c)(2)(F)

[19] 45 CFR 98.33(a)(2)

[20] See https://childcare.gov, which is mandated by §658L(b) of the CCDBG Act.

[21] 87 FR 41878; Sarah Sattelmeyer & Brian Denten, “Policymakers Should Consider Impact of Growing Student Loan Balances on Borrowers and Taxpayers,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, April 8, 2020, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2020/04/08/policymakers-should-consider-impact-of-growing-student-loan-balances-on-borrowers-and-taxpayers.

[22] 87 FR 41878.

[23] Sen. Patty Murray et al. to Sec. Miguel Cardona, July 1, 2021, https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Senate%20Dem%20Student%20Debt%20Relief%20Comment%20Letter%20to%20ED%201-July-2021.pdf.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Sen. Patty Murray et al. to Sec. Miguel Cardona, July 1, 2021, https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Senate%20Dem%20Student%20Debt%20Relief%20Comment%20Letter%20to%20ED%201-July-2021.pdf.

[26] The Department’s preamble states that “[t]he Department is concerned that we should not be distributing new loans if borrowers have a demonstrated disability that prevents them from working and ultimately repaying that loan.” However, the Department’s proposed regulations do not prevent the disbursement of the new loan in these circumstances, they simply reinstate the repayment requirement for any previously discharged loans.

[27] Cory Turner, “When colleges defraud students, should the government go after school executives?” NPR, March 1, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2022/03/01/1062679587/for-profit-colleges-student-loan-borrowers-fraud.

[28] Sen. Patty Murray et al. to Sec. Miguel Cardona, July 1, 2021, https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Senate%20Dem%20Student%20Debt%20Relief%20Comment%20Letter%20to%20ED%201-July-2021.pdf.

[29] Sec. 437(c)(1) of the HEA applies to FFEL Program loans. Sec. 455(a) of the HEA applies the same terms and conditions to Direct Loans. Similar requirements are established for Perkins Loans under Sec. 464(g).

[30] Sen. Patty Murray et al. to Sec. Miguel Cardona, July 1, 2021, https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Senate%20Dem%20Student%20Debt%20Relief%20Comment%20Letter%20to%20ED%201-July-2021.pdf.

[31] 34 CFR 600.2; 34 CFR 602.24.

[32] 34 CFR 600.2; 34 CFR 602.24.